Over 130 curse tablets have been discovered in the Sacred Roman Spring at Bath and this summer I had the opportunity to work with the museum’s collection team on the Curses Project and handle some of these fascinating objects.

What are curse tablets?

Curse tablets were a common feature throughout the

Greco-Roman world and were an outlet for people to air their anxieties and

grievances. They are small sheets of metal, often lead, which contain inscriptions

appealing to a deity to cast influence or revenge on another individual. They

were usually deposited at religious sites and were often buried or thrown into

water so the unique natural hot spring at Bath would have been the ideal

location for this ritual. Most of the legible curse tablets at Bath address the

goddess Sulis Minerva and relate to the theft of an object.

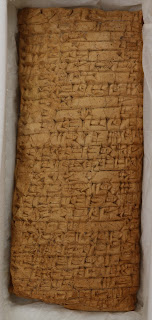

Curse tablets on display at the Roman Baths museum.

What can they tell us about the Romans?

One aspect of Roman life which they can tell us about is

literacy. It is generally believed that literacy levels throughout the Roman

world were low and that it was mostly the upper class that were able to read

and write. However, only two tablets at Bath were written by the same hand which

suggests that there was a significantly higher proportion of the population

that could write than what is usually assumed. Many of the curse tablets are

thought to have been petitioned by the local native population and this is supported

by the lack of Roman name formation within the inscriptions and the mention of

low value objects.

Who or

what is Vilbia?

One of my favourite curse tablets and the first to be

discovered at Bath in 1880, is the tablet concerning the theft of Vilbia. The

word ‘vilbia’ has proven to be quite problematic.

Some believe that the tablet refers to the theft of a woman, whilst others argue that the word refers to an object as ‘vilbia’ is similar to another British name for a small tool. Such debate which focuses on the language within this inscription shows how hard it is to interpret literary evidence and highlights the dangers in making assumptions about ability. Although it is one of the more legible tablets found at Bath, there are instances where the inscriber has gone over letters to possibly alter mistakes.

Theft of a Hooded Cloak

|

| "To Minerva the goddess Sulis I have given the thief who has stolen my hooded cloak, whether slave or free, whether man or woman. He is not to buy back this gift unless with his own blood." |

These small tablets offer us insight into an array of

topics regarding Romano-British life and I encourage you all to come and see

them for yourselves at the Roman Baths.

Kate

Placement student